Cyrus Dallin's Original "Captured But Not Conquered"

Cyrus Dallin (Springville, UT 1861 - Arlington Heights, MA, 1944)

Captured But Not Conquered (1918)

Bronze, Gorham Founders

32 1/2 in high

Signed: “CE Dallin, 1918” #3 of 5

PROVENANCE

Cyrus Dallin

Mrs. Prudence Halyburton

Edgar A. Halyburton

Private Collection, Lakewood, California

About the Work

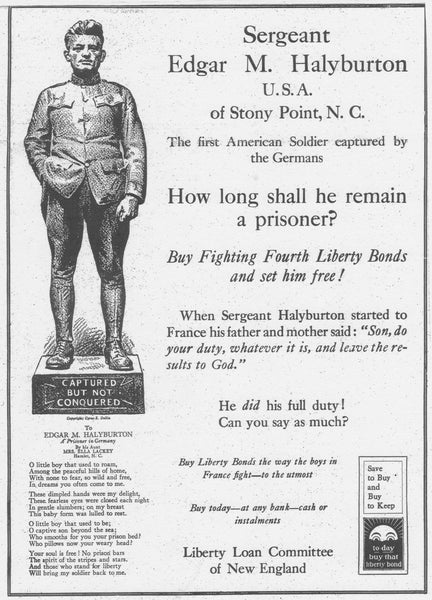

It is remarkable and appropriate that this sculpture should surface the same year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ending of World War I. Titled “Captured But Not Conquered,” it depicts, Edgar M. Halyburton, the first American prisoner of War in the conflict. After his capture, German propagandists took and distributed Halyburton’s image in hopes to demoralize newly-arrived American troops. But the effort backfired fantastically. Within days, the photograph as re-appropriated by the allies and reproduced internationally: an American soldier standing tall with one hand in this pocked and the other clenched in a fist at the side was seen as a message of defiance against the odds. Although it is certain that this statue is one of the original three to five made by the sculptor Cyrus Dallin and cast by Gorham, we now believe it was the same sculpture given by Dallin to Halyburton’s family.

In late November 1917, seeing the photograph of the first American POW in a in a Boston paper, Cyrus Dallin immediately began working the image into a sculpture. Dallin had achieved national recognition for his statue of the Angel Moroni atop the Salt Lake Temple, a depiction of Isaac Newton at the Library of Congress and a monumental equestrian statue of the American Patriot Paul Revere. The latter was unveiled in Boston only two months before began work on “Captured But Not Conquered.”Dallin used his son, Arther — who would himself serve in World War I as an ambulance driver and later as a pilot in World War II — as a body double for the POW. The sculptor used the photograph to create the face and put the phrase “Captured But Not Captured.”

How Dallin’s project came to the attention of the Directors of the newly created Federal Liberty Loan — later known as Liberty Bonds — program, is unknown. Tasked with raising funds for the war effort, through government-backed, low interest loans, the program commissioned five original bronze statues from Dallin, which were cast by the Gotham Manufacturing Company. Hundreds more versions of the statue were cast in plaster by Caproni Brothers of Boston and distributed throughout the United States, at post offices and recruitment offices, along with posters of the Statue. It was not until the Liberty Loan program was well under way that Dallin received a letter from Charles O. Carrier, stating:

Mr. Dallin, Having seen a reproduction of your statuette "Captured But Not Conquered,” I wish to pay you a compliment, but am at a loss for words. With the original of the photograph, I am personally acquainted, and you have not only reproduced the features and expression, but his actual character is embodied in the same. I thought perhaps you would be pleased to learn his name which is Edgar M. Halyburton, son of Mrs. Prudence Halyburton of Stony Point, NC, to whom I have mailed a copy. (Reproduced in Edgar Halyburton and Ralph Goll, Edited and annotated by Jonathan Gawne. Shoot and Be Damned Framingham: Ballacourage Books, 2014.)

Upon receipt, Dallin immediately sent a copy of the letter to John K. Allen, Publicity Director of the Liberty Loans in New England, who had already reproduced and distributed plasters and posters of the statue as part of the Liberty Loans Second Campaign. Allen responded:

Our use of the statuette struck a high note in publicity, and those which were sent to various cities in New England have found their way either into public libraries or art museums, and the Liberty Loan Committee has received appreciative letters. (Reproduced in: Edgar Halyburton and Ralph Goll, Edited and annotated by Jonathan Gawne. Shoot and Be Damned Framingham: Ballacourage Books, 2014.)

For the Third Liberty Loan Campaign, Edgar Halyburton’s name was put alongside Dallin’s statue for the first time. And, putting a name to the already famous sculpture led to increased curiosity about this one-anonymous soldier’s experiences.

The capture of Sargent Edgar Halyburton came as a great show to Americans who had only recently and reluctantly entered the war. From the onset of the war in 1914 until April 6, 1917, the United States was official neutral in the European conflict. It was not until German forces had sunk a series of commercial and civilian sea vessels that public opinion shifted. And, even then, it would be another six months until American troops were sent to the front lines.

The Capture of Halyburton

Sergeant Halyburton was a doughboy; a regular member of the army with no special education or training. As a member of North Carolina’s Company F, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, he was among the first hundred US soldiers to relieve French soldiers in the trenches. On November 17, 2017, they were stationed in Valhey, located in the disputed Lorraine region between France and Germany.

It was an unfortunate and eventful day. Years later, Frank Coffman, a member of Halyburton’s platoon: “Entering that sector but four hours previously as green troops, most of us having been in the service a short time prior to our leaving the State, daybreak brought to us all the reality of the horror and cruelty of the world we had to do, and changed us from callow youths to grim and silent men. . .”

He went on to give a detailed account of events the night Halyburton was taken captive:

The next morning we carried our three dead comrades back to the rear and buried them with simple military honors. The French General commanding our sector, in a short speech of beautiful sentiment, expressed the wish that the bodies of those three boys should forever remain in the soil of that country which they came so far to protect and for which they gave their lives; that their grades should always be a shrine of hallowed ground to which his people could go in a spirit of gratefulness and sorrow. (Frank Coffman. “And Then the War Began” American Legion Magazine ( 13 JAN 1922), 13.)

Once captured, Halyburton and his fellow American prisoners were put too hard labor. The German army was experiencing severe food shortages, had eaten all non-essential animals for survival. In their place, POWs were used as human pack animals, living off the scraps of starving German troops.

As the senior ranking member, Halyburton organized his men, a number that grew over the ensuing months from the initial eleven to more than 2,200. According to one report, Halyburton used his leadership not only to carry out German officer instructions for labor, but organized a resistance to German propaganda by smuggling out news of enemy failures, shortages, and movements to Allied newspapers. He oversaw the welfare of his men, created a behind-the-lines intelligence service, aided in the escape of many prisoners, and thwarted German collaborators. (Greg Eanes. “Remembering First World War POWs in a noble mission” Leigiontown USA, 19 SEP 2018.)

For his efforts Halyburton was the first enlisted man (i.e. non-officer) to receive the Distinguished Service Medal. In a letter accompanying the award, General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front, wrote:

Your loyalty and self-sacrificing spirit of devotion to the interest of American soldiers who were prisoners in Germany during the hostilities is worth of the highest tradition of American manhood and patriotism. Confronted with the difficult and serious problems of discovering and exterminating the enemy propaganda, made in endeavors to stifle the morale of the American, you did not waver for an instant, but remained steadfast to your purpose and accomplished a most commendable service to your nation.I have just learned with great pleasure of your magnificent and noble conduct while you were a prisoner of war in the hands of the enemy.

Halyburton was honorably discharged from duty at the end of the war and returned to the United States to find that he had become a celebrity, in large part owed to Dallin’s sculpture. In his autobiography, Shoot and be Damned (1932), he wrote:

I had heard of the sculpture after my repatriation, but not until now had I seen a copy of it. One stood in the living-room of our home. It had been sent to my mother by the sculptor, Dallen [sic.], of Boston, who used as a model a picture taken of me by the Germans the day of my capture. Replicas of the statue had been exhibited in Liberty Loan and Red Cross. (Edgar Halyburton and Ralph Goll, Edited and annotated by Jonathan Gawne. Shoot and Be Damned Framingham: Ballacourage Books, 2014.)

After the war, Halyburton lived a peripatetic existence, taking jobs and losing them due to nervous periods that, in retrospect, appear to be the clear results of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. He married. But, never had children, and was buried in 1945 at the National Cemetery in Los Angeles with full military honors.

Halyburton’s service, first anonymous and then proven courageous, was the story of so many. In all, 4.7 million Americans served over 200 days in World War I, with 116,510 losing their lives.Cyrus Dallin’s work not only magnified the life of Halyburton, but the stories of every humble soldier — the doughboy — who had served and sacrificed in the War to end all wars.